This study guide considers how artists attempt to bring visibility to the unjust histories and social, political, and economic systems and histories that structure the criminal justice system in the U.S. The guide begins with a brief definition of the term “prison industrial complex.” It then considers how artists connect the history of slavery and its economic legacies to the prison industrial complex, suggesting that prisons are part of the unfinished project of freedom in the U.S. Relevant short clips from artist interviews are included with each section, and the embedded links will take you to more information about the artworks and artists mentioned.

What is the Prison Industrial Complex?

Pause

What do you already know about the Prison Industrial Complex? Before we define it, take a moment to think about what it may encompass.

"The prison has become a black hole into which the detritus of contemporary capitalism is deposited." —Angela Davis

Since 1980, the number of people in United States prisons has increased more than 500%, despite a crime rate that has been falling steadily for decades. This immense increase in incarceration has been the result of changes in law and policy, not changes in crime rates. In fact, there is a profound disconnect between crime and incarceration throughout the nation, which has been made clear in countless studies and with overwhelming evidence that large-scale incarceration is not an effective means of achieving public safety.

If the numbers of people in prisons have little relation to crime rates, and if incarceration has proven ineffective in increasing public safety in the U.S., why are there so many prisons and so many people inside of them?

For much of these study guides we refer to “prisons” or “the prison system,” but to answer the question of why we have prisons if they are not a solution for crime, it is important to remember that the prison system is more far-reaching than the prison structures themselves. The “prison industrial complex” (PIC) is a term that has been used since the 1990s to describe the complex and overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, detention, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social, and political problems.

Thinking in terms of the PIC allows us to address the economic, political, and ideological structures that support the U.S. prison system. The PIC encompasses all aspects of the criminal justice system, including laws and legislature, police officers, prison employees, judges, and courts, and it also includes the corporations that profit from prison building and prison labor as well as the manufacturers of equipment used by guards and police. Additionally, the PIC consists of the political power derived from issues surrounding prisons and policing. This is because policies, positions, and legislation around crime and punishment profoundly influence voting and fundamentally drive politics in the United States. As Ruth Gilmore explains, prisons and crime are strategically used by politicians and governments “to legitimize the state.”

In other words, and as the term “prison industrial complex” suggests, prisons, policing, and the entire criminal justice system are central to the social, economic, and political structures of the U.S., despite failing to address the issues of public safety and crime that are their ostensible purpose. As Angela Davis puts it, the prison industrial complex “generate[s] huge profits from processes of social destruction.” The profits she is referring to surpass the financial.

Reflect

How did this definition of the "prison industrial complex" differ from or align with your expectations? Where can you see the PIC in your own community or in recent U.S. politics?

From Slavery to the Prison Industrial Complex

“How does visual art help to reveal the depth of devastation caused by our nation’s punishment system?” —Nicole Fleetwood, Professor of American studies

“The 3,000 women in my prison are disproportionately poor and minority. Prison marks a separation in our society between the “haves” and the “have-nots,” between those who walk free and those of us held captive. —Beverly Henry, formerly incarcerated woman and Barring Freedom contributor

Activist Mariame Kaba describes the violent and destructive history of prison and policing in the U.S. as connected to the history of slavery:

“There is not a single era in United States history in which the police were not a force of violence against Black people. Policing in the South emerged from the slave patrols in the 1700 and 1800s that caught and returned runaway slaves. In the North, the first municipal police departments in the mid-1800s helped quash labor strikes and riots against the rich. Everywhere, they have suppressed marginalized populations to protect the status quo.”

The prison industrial complex emerged, to summarize this brief historical overview, to enforce racist social hierarchies and unequal economic structures.

Nowhere are the connections between the nation’s histoory of slavery and the present prison industrial complex made more explicitly than in documentary photographers Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun’s ongoing series >Slavery: The Prison Industrial Complex>.

This series of photographs was taken over four decades in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, which is called Angola after the former plantation where the prison is currently located. The plantation was named for the country of origin for most of the people enslaved there. McCormick and Calhoun’s images capture how Angola reveals slavery’s afterlife. The photographs show the men who are incarcerated in the prison, 82% of whom are African American, working the 18,000 acres of Angola in conditions that seem to have changed very little over the 150 years since slavery was abolished in the United States. Unfree men continue to work the field of this plantation-turned-prison under the watchful gaze of armed White officers who tower over them on horseback. The prison laborers are paid as little as two cents, and no more than one dollar an hour for this strenuous work.

The black and white photographs seem to give viewers a glimpse into the nation’s troubled history, not of what is unfolding in the present. Calhoun and McCormick stress that they intend for viewers to struggle to believe that their photographs are of workers in the present moment. Calhoun states:

“They say, ‘That was a long time ago, huh?’ And I say ‘No, it goes on every morning. Every morning they got a line running in the fields somewhere. In Angola, it's mandatory that you work, so every morning you gotta get up behind that horse.’ Slavery is not over.”

Sharon Daniel’s artworks center the voices of incarcerated individuals describing their experiences of injustice and the economic oppression of the PIC. Her series Undoing Time was inspired by an op-ed written by Beverly Henry, a woman formerly incarcerated at Central California Women's Facility (CCWF), who worked sewing U.S. flags in a prison factory. The op-ed speaks to the failure of the U.S. government to offer liberty and justice to all. Daniel explains that after reading the op-ed, she wanted, “...to see it embroidered into the stripes of every flag that came out of that factory.” In response, Daniel’s sculptures use these flags manufactured within the California prison system, stitching into them various testaments to the unjust system.

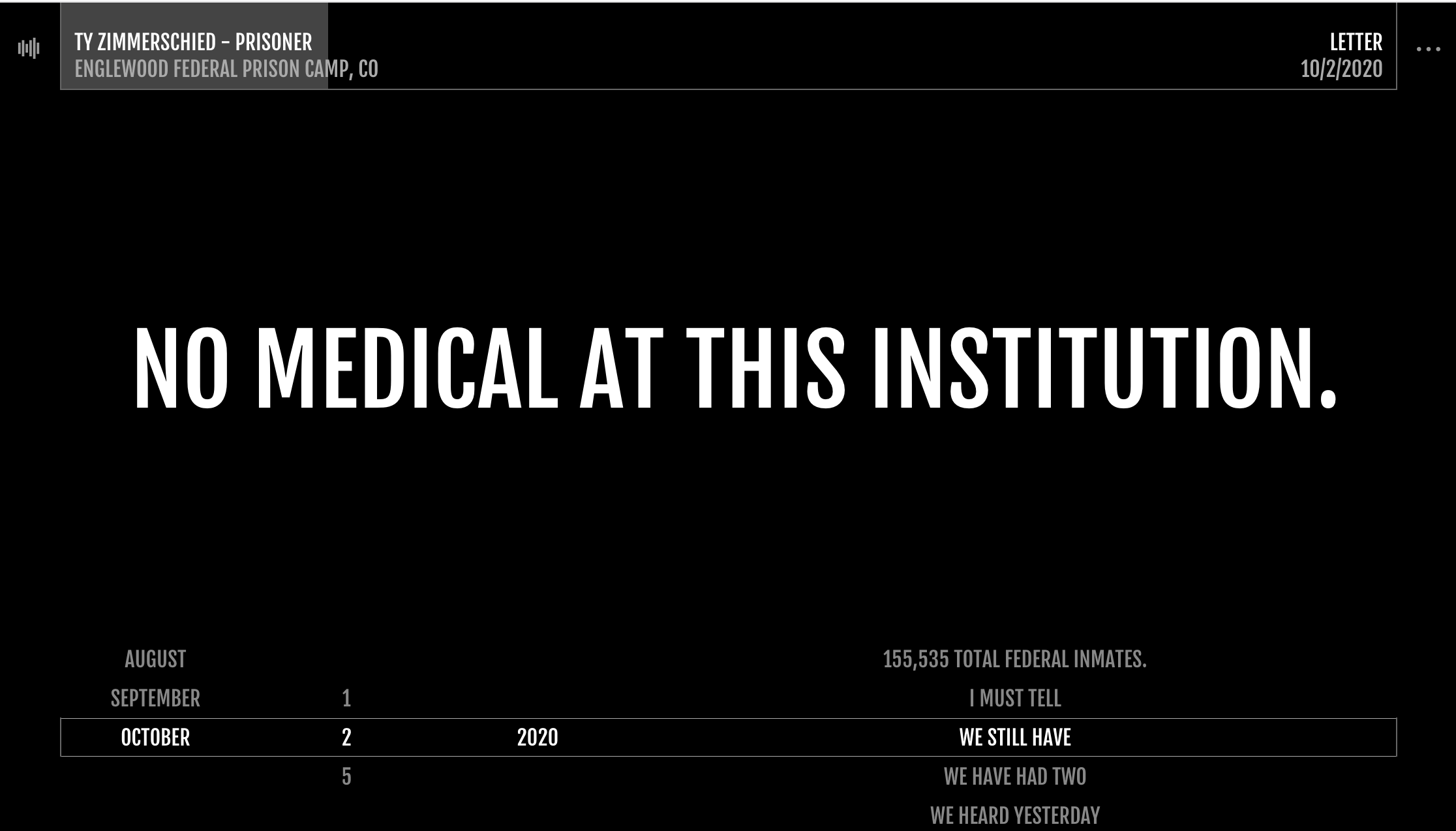

Daniel’s newest work EXPOSED is a

website that documents the spread of COVID-19 inside prisons, jails, and detention centers across the U.S. This

harrowing artwork calls attention to the way our society treats those who are incarcerated as disposable.

Throughout the pandemic visitation and education programs within prisons have been halted, however, factory labor

continues. A recent Los Angeles Times

article reported on mask and

hand sanitizer production in a California prison. Robbie Hall, an incarcerated woman who worked in the

factory and contracted COVID-19, described the operation as being, “…like a slave factory. The more you give them, the more they want.”

Explore the work here.

If prison labor has a clear relationship to slavery, comparing the full PIC to slavery does little to account for the fact that less than half of incarcerated people work. In the most recent available statistics, only 800,000 people incarcerated, out of a population of about 2.3 million, had jobs within their facilities. The majority of America's pprison population remains locked in cells and dorm rooms, without occupation, costing the government vast amounts of money.

The Redaction Project, a collaboration between visual artist Titus Kaphar and poet and attorney Reginald Dwayne Betts, offers insights into how racism, economics, and the PIC are linked in ways that do not look like slave labor.

_diptych_1.jpg)

_diptych_2.jpg)

For these prints, the collaborators transformed court documents into haunting portraits. Each work combines a delicate line etching superimposed with words extracted from lawsuits filed by the Civil Rights Corps on behalf of people incarcerated because they lacked the means to pay their court fees. As Michelle Alexander states: “Most Americans probably have no idea how common it is for people to be convicted without ever having the benefit of legal representation.” In Kaphar and Betts's prints, this unjust reality is poetically unmasked by redacting the superfluous text from the court documents to leave just the most salient and tragic details. In Untitled (Alabama 6.1), 2019, the fragments of text reveal a father who was jailed for 23 days over a traffic ticket and accumulating fines of $1600, who was ordered to clean blood and feces from the jail floor while detained, and then lost his job while jailed. In Untitled (Missouri 3), the text ends “threatened, abused/ left to languish/ family members could/ buy their freedom.” The works bear witness to the criminalization of poverty and the ongoing reality that freedom is a question of financial means. The fact that the victims of this injustice that Kaphar and Betts's work portray are all African American also depicts how racism is used to justify this twisted economics.

Reflect

How do you feel after looking at these different artworks? Did any of them reveal something new about the prison system to you?

An Incomplete Freedom

“I think of the flag as a kind of mask and a veil. It screens out the view of the real history of our country in terms of its origins in genocide and slavery.” Sharon Daniel

“We’re never actually going to build anything until we contend with the faulty premise on which this nation was founded.” Sonya Clark

Freedom in the United States has always been defined in relation to various forms of racialized unfreedom. Whether looking at chattel slavery, the genocide and resettlement of Native Americans, the internment of Japanese Americans, segregation and red lining, or the current crises of mass incarceration and detention in both prisons and at the border, the U.S.’s vision of full and free citizenship has been crafted in contrast to a designated “other.” These exclusions are foundational to the nation and therefore to the ways that freedom and democracy have been practiced and built. Artists in Barring Freedom look at the tensions between U.S. claims to liberty and justice and the reality of existing practices. In doing so, they also open the possibilities for envisioning freedom anew.

Pause

Before you move on, take a moment to define freedom for yourself. How do you know if you are free or not? How are your freedoms intertwined or in tension with the freedoms of others?

Barring Freedom includes several artworks by Sonya Clark all of which consider the ongoing promises and failures of "justice and freedom for all" in the United States. In the interview segment below, Clark discusses her sculptures Edifice and Mortar and Three-Fifths, both of which draw attention to the continual strive towards democracy and equality, and the unfinished nature of emancipation. She says:

"Every day, all day, as America tries to work its way towards democracy, it has to contend and redress the issues of racial disparity, racism, racial injustice, and racial inequality and every time it doesn't the democracy falters. And we haven't gotten there yet."

In her extended interview, Clark discusses how the materials she uses, particularly human hair, carry complex and dense histories into her works.

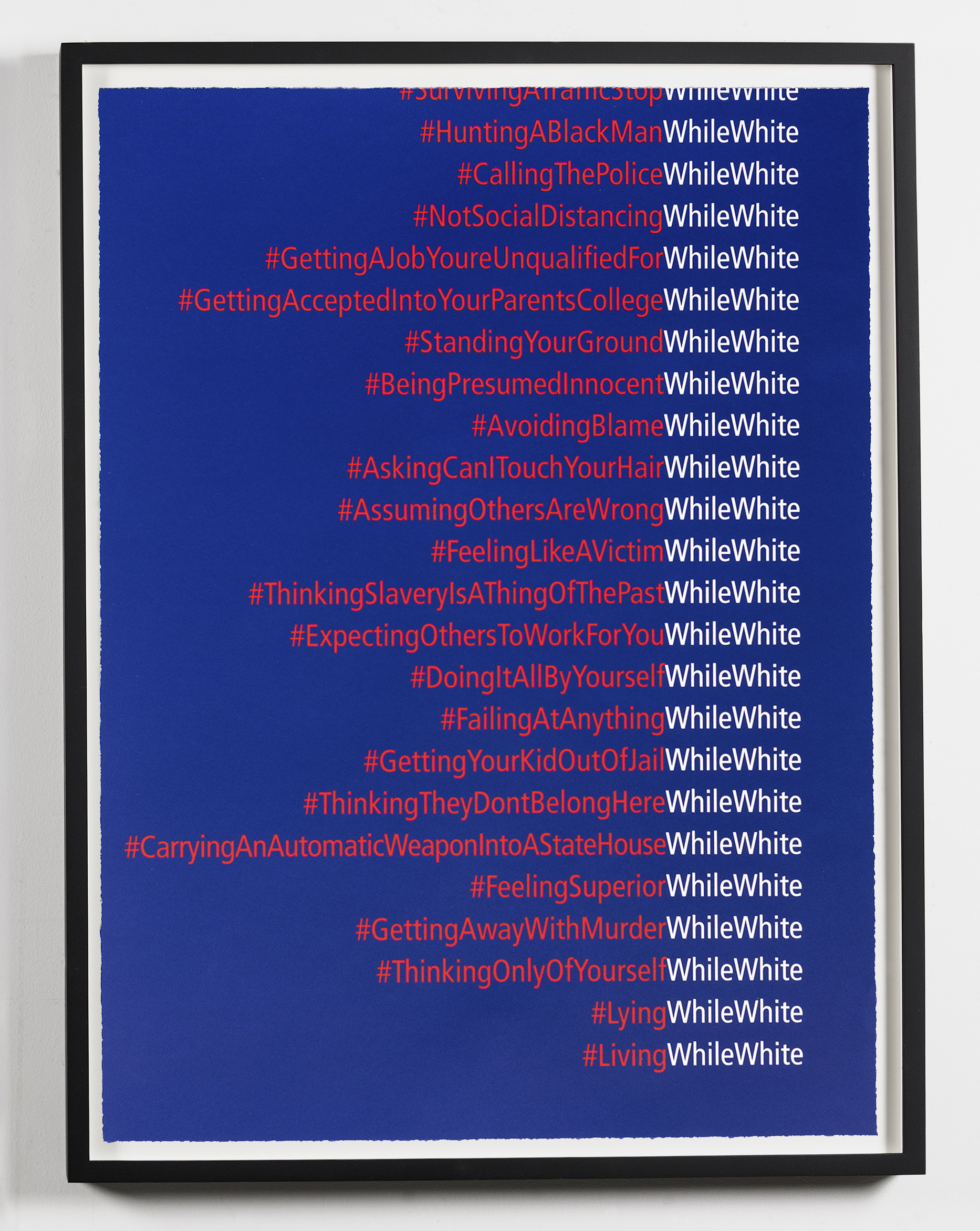

In his screen print #WhileWhite, Dread Scott powerfully argues that it is a privilege to think that slavery is over. The piece uses the repeating hashtag “WhileWhite” in reference to the ways that images and activism circulate online, but here the elaborated hashtags refer to privileges that have been granted to White people. Some of them are privileges that may be taken for granted, such as being presumed innocent in a court of law, or which may be uncomfortable to see in oneself, such as avoiding blame for getting a job you are unqualified for. Others reference specific acts of violence against Black individuals perpetrated by White individuals in the United States. Taken together, the list holds up a mirror to freedom in a white supremacist culture: thinking only of oneself and treating perceived “others” as disposable. In the context of COVID-19, the prevalence of this mentality is hard to ignore.

In order to find different visions of freedom, Dread Scott turns to history. In the video below, he discusses his Slave Revolt Reenactment as an opportunity to learn from the enslaved. Scott argues that writings on freedom by men such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, both of whom owned slaves, are limited by their oppression of others while, in contrast, the enslaved held the more radical and expansive vision of freedom, stating, “A project like Slave Rebellion Reenactment actually is calling on people to learn from people who fought to overthrow a system of enslavement.”

Reflect

Dread Scott upends U.S. history by suggesting that our heroes shouldn’t be George Washington and Thomas Jefferson but the many enslaved people who tried to revolt and overturn the system. In your opinion, who are the visionaries of freedom in our current moment?

Cited Readings

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press, 2012.

- Bozelko, Chandra. “Think Prison Labor Is a Form of Slavery? Think Again.” Los Angeles Times, October 20, 2017, sec. Opinion.

- Davis, Angela Y. Are Prisons Obsolete? New York: Seven Stories, 2003.

- Feldman, Kiera. “California Kept Prison Factories Open. Inmates Worked for Pennies an Hour as COVID-19 Spread.” Los Angeles Times, October 11, 2020, sec. California.

- Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2020.

- Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. American Crossroads 21. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

- Kaba, Mariame. “Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police.” The New York Times, June 12, 2020, sec. Opinion.

Related Resources

- NAACP, Criminal Justice Fact Sheet

- New York Times 1619 Project

Other Study Guides