This study guide introduces the theme of prison abolition, as it appears in the exhibition Barring Freedom. There is a brief definition of "prison abolition," followed by a summary of how some of the artists in Barring Freedom invite reflection on a future beyond prisons. Relevant short clips from the artist interviews are included with each section, and the embedded links will take you to more information about the artworks and artists mentioned.

What is Prison Abolition?

Pause

Before reading, pause a moment to consider what you think it would mean to abolish prisons. What do you think the goals are of the abolition movement?

"Do you believe in universal healthcare, housing for everyone, and a universal income? Would you want those things in this world? Would you trade prisons and police for that? That’s what abolition is." —Emile DeWeaver, Co-founder Prison Renaissance

"We want a society that centers freedom and justice instead of profit and punishment."[1] Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Professor of Geography at the CUNY Graduate Center, and and James Kilgore, Media Justice Fellow at Media Justice

In their article "The Case for Prison Abolition," scholars Ruth Wilson Gilmore and James Kilgare argue that prisons, jails, and policing in the United States cannot be understood or improved when viewed alone—these structures need to be understood within, “the entire ecology of precarious existence” that produces incarceration. Instead of focusing only on tearing down the physical walls of prisons, jails, and detention centers, the prison abolition movement seeks to eliminate the need for prisons. It takes as its central premise that to create an equitable society, the core problems that lead to incarceration must be addressed. In the words of activist and scholar Angela Davis, we must, “imagine a constellation of alternative strategies and institutions, with the ultimate aim of removing the prison from the social and ideological landscapes of our society.”

Abolitionists strive to envision and build social structures that would make prisons and policing obsolete. Their aim is to redesign society so that problems such as poverty, mental health issues, homelessness, and lack of access to education are not solved through punitive means like imprisonment, but instead through universal and justice-based programs. Abolitionist tactics include activism aimed directly at the systems of incarceration and policing and include: stopping the construction of new prisons, eliminating mandatory minimum sentences, and introducing restorative justice models. This also includes work directed away from prisons, such as, increasing investment in schools, mental health services, and other social programs intent on ending inequalities.

REFLECT

How did the definition of "prison abolition" given here differ from or align with your expectations? How do you feel about the propositions being made?

How do we imagine a landscape without prisons?

“Art reminds us we are not obligated to recognize what is given simply because it is given. Rather, it helps us cultivate the imagination – to make something new of the old.” —Angela Y. Davis, political activist and scholar

When Angela Davis says that an abolitionist approach requires us to, “imagine… alternative strategies and institutions,” she is suggesting that abolition is a creative project. It requires the ability to dream outside of how society is currently organized and think beyond the belief and value systems that position prisons and jails as solutions to social problems. She also cautions us that, “dangerous limits have been placed on the very possibility of imagining alternatives” to prison. What are these “dangerous limits"?

In his full interview, Emile DeWeaver discusses what he calls, “our imagination problem.” He points out that the project of prison abolition is ultimately the reopening of imaginative possibilities that have been closed off through settler colonialism and white supremacy. These systems of inequality have had lasting effects on how we see and understand the world, including how we imagine our responsibilities to other people and our ideas of crime and punishment. In the words of scholar Saidiya Hartman, writing on the abolitionist imaginary, “What is required is a remaking of the social order, and nothing short of that is going to make a difference."

Artists involved in Barring Freedom work to interrogate and stretch our capacity to imagine a world beyond prisons through a variety of approaches.

Artist jackie sumell, invites people to imagine a landscape without prisons through collaboratively planting Solitary Garden with a solitary gardener—someone who is currently in solitary confinement. At UC Santa Cruz, students, faculty, staff, and community members have worked with Tim Young, who is currently incarcerated in San Quentin. Through the process of writing letters to Young and working together in the soil, participants have formed relationships around and through the garden. In Solitary Garden, abolition emerges as a continuous process of nurturing and solidarity. In Tim’s words,

Do unto me As you would do unto the flowers, plants, crops, and seeds And I too, shall flourish.

Planting seeds signals a belief in a better future, brought into being through the ongoing work of care and attention.

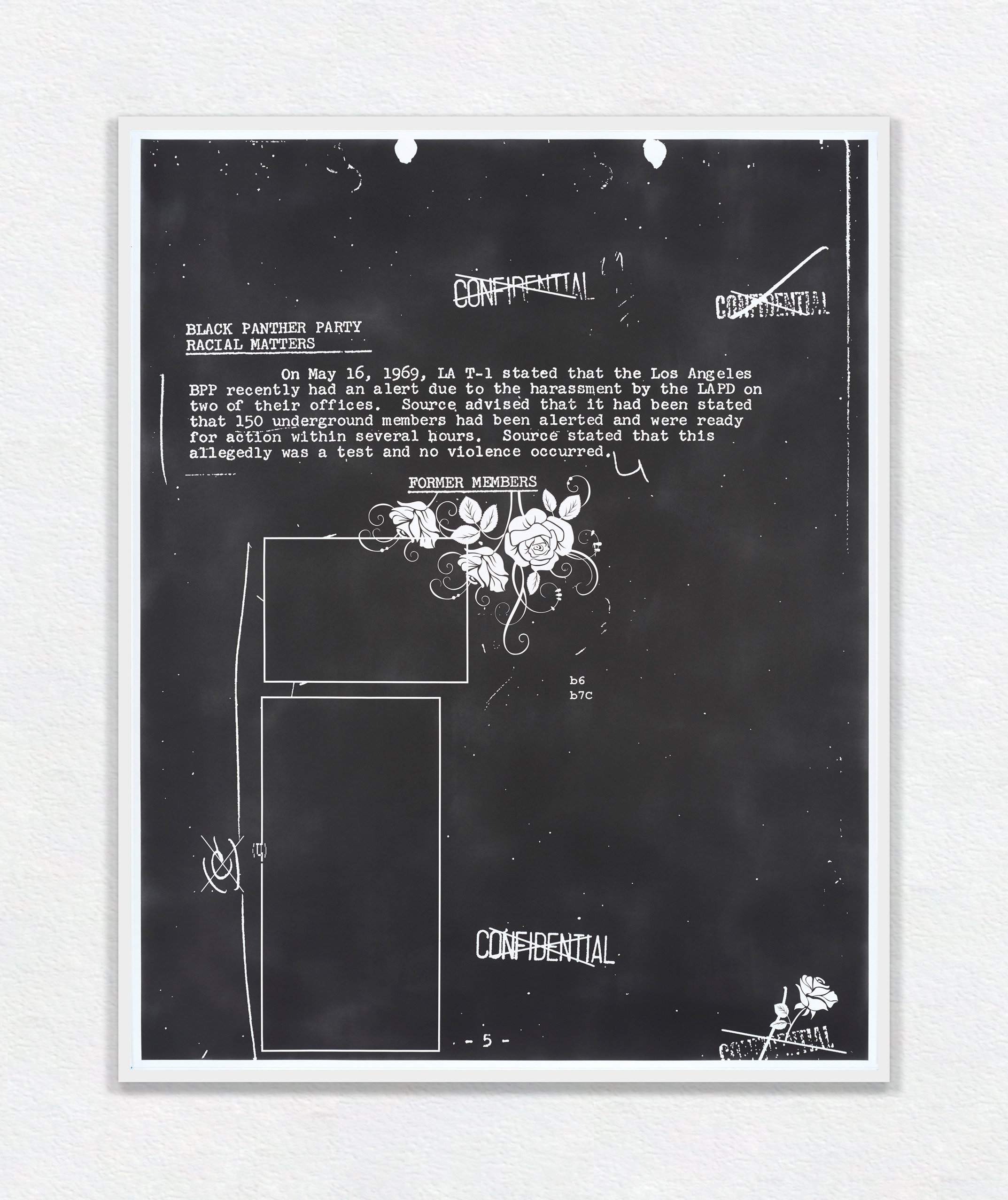

Flowers also appear within Sadie Barnette’s drawing FBI Drawings: No Violence, 2020, the latest project in her ongoing engagement with her father’s FBI surveillance file that was accumulated during his time as a member of the Black Panther Party. Here, Barnette transforms a page of his FBI file into a meditation on the damage and limits of state surveillance. The negative space of the page is reversed, and the space between the words becomes a rich black expanse, both drawing attention to the act of surveillance (particularly what Simone Browne calls, “racializing surveillance”) and functioning as a veil against it. The words “Former Members” are adorned with flowers, suggesting a memorial to those who lost their lives at the hands of the FBI and perhaps to the party itself, but the flowers also gesture to the possibility of new growth from this painful history. In a a recent interview, Barnette said, “I’m dreaming of something so fundamentally different that it is still a dream.”

Another memorial that projects the possibility of a more beautiful future is Sanford Bigger’s luminous BAM (Seated Warrior), 2016. This figure stands 6' 6" tall, despite missing a leg and the segment of one arm. It is part of Biggers’ larger series of works in which he dipped wooden figurative sculptures from Africa into a thick wax, had the pieces shot with a gun, and cast the resulting fractured objects in bronze. The sculptures connect contemporary and ongoing police violence to slavery and the abduction of millions of Africans that occurred over centuries. Deeply troubling, but also stately and tender, the works radiate power. They reflect an Afrofuturist vision, present in other works by Biggers, in which the past returns to the future remade.

Walking the viewer through her studio notes in the video below, Patrice Renee Washington asks, “How do we fit within existing systems, and how do we go about creating new systems?... How do we subvert what is already within the world?” Washington’s ceramic reinterpretations of exercise equipment are one attempt to answer these questions, suggesting a softness and malleability to that which we see as concrete and immovable.

Lastly, in the interview on her artist page, Maria Gaspar introduces her recent project Disappearance Jail, 2021, which, through simple gesture of redacting the image of Cook County Jail, invites hopeful reflection on the potential of physically removing the prison from our landscapes. In addition, she discusses her open- ended and collaborative approach to community-based work as a process of abolition that undoes the forms of division that undoes the forms of division that prison walls encourage.

Reflect

Which of these artworks or approaches speaks to you? Why? How does it encourage you to think about our prison system or our society at large?

Remaking the World

“We’re not going to just be able to get rid of prisons in one day, overnight. This is going to be a process.” —Patrisse Cullors

In "What Abolitionists Do?", scholars and activists Dan Berger, Mariame Kaba, and David Stein make the argument that far from being utopian dreamers, prison abolition activists are pragmatic organizers, leading the way in mobilizing for concrete policy changes. The artists in Barring Freedom also reflect this engaged and grounded method. Artist Ashley Hunt describes artists and activists, “as two positions within which people make the world and reproduce it,” emphasizing the interrelationship and complementary activities of both. Hunt’s exhibitions often include contributions from local activists that amplify abolitionist projects happening in the surrounding area. Even though Hunt’s photographs draw attention to the ubiquity and normalization of incarceration in our landscape, he frames several of his prints within the context of ways critiques of the prison system become visible in our cultural landscape, adding to his “atlas of incarceration” the record of dissent.

Tapping into the potential synergy between artists and civic participation, Hank Willis Thomas is among a collective of Wide Awakes, an open-source network inspired by the 1860 abolitionists but who are imagining forms of political action in the present. The video below gives a taste of what they are planning. In his extended interview, Thomas also compares his use of prison uniforms in his artwork to how nineteenth century abolitionists circulated objects of torture to draw attention to the cruelties of enslavement and the plantation system.

Finally, though there may be an affinity between art and activism, it is also important to remember that the artworld and art museums are bound up in the power structures of white supremacy and anti-Blackness that undergird American society more broadly. Barring Freedom artist Dread Scott addresses this tension in the video below, discussing the reticence of U.S. institutions to exhibit his work A Man Was Lynched by Police Yesterday, 2015. Are museums ready for the real self-reflection and the tangible change that a reckoning with the Black Lives Matter movement demands?

Reflect

What are the ways you can think of that museums are or have been implicated in systems of oppression and exploitation? How would you imagine museums for an abolitionist future?

Cited Readings

- Berger, Dan, Mariame Kaba, and David Stein. "What Abolitionists Do," Jacobin, August 24, 2017.

- Cullors, Patrisse. “Black Lives Matter Co-Founder Patrisse Cullors Explains Her Fight for Prison Abolition.” Teen Vogue, February 22, 2019.

- Davis, Angela Y. Are Prisons Obsolete? New York: Seven Stories, 2003.

- Davis, Angela Y. “Politics

& Aesthetics in the Era of Black Lives Matter.” NYU, November 5, 2018. .

- Gilmore, Ruth Wilson, and James Kilgore. “The Case for Prison Abolition.” The Marshall Project, June 19, 2019.

- Hartman, Saidiya. “Saidiya Hartman on Insurgent Histories and the Abolitionist Imaginary.” Artforum, July 14, 2020.

- Zimmerman, Emily, and Sadie Barnette. “The Politics of Sight.” BOMB Magazine. April 21, 2020.

Further Resources

- Critical Resistance, Abolish Policing

- Abolition Journal Study Guide

- Change the Museum, Instagram Account

Other Study Guides