This study guide looks at artists and artworks that blur the border between inside and outside the prison, making visible the lived experience of incarceration and its effects. This includes work by artists who were formerly incarcerated or who are collaborating with people currently in prisons, as well as works by artists who have otherwise been personally impacted by incarceration. Short clips from artist interviews are included, and embedded links offer more information about the artworks and artists mentioned.

Who do We Incarcerate?

"It is precisely the abstraction of numbers that plays such a central role in criminalizing those who experience the misfortune of imprisonment. There are many different kinds of men and women in the prisons, jails, and INS and military detention centers, whole lives are erased by the Bureau of Justice Statistics figures." Angela Davis, Political activist and scholar

"When we think “prisoner,” we think poor person, we think minority, we think oppression. Why don’t we think journalist, economist, legal scholar? …We are as creative as you, we are as diverse as you, we dream like you. We are you.." Emile DeWeaver, Co-founder Prison Renaissance

Pause

What images come to mind for you when you hear the word prisoner? Why do you think that Emile DeWeaver generally avoids this term?

The quote above is an excerpt from Emile DeWeaver’s introduction to Prison Renaissance’s sound installation Metropolis. DeWeaver reflects on the term “prisoner” and how it distorts the image of incarcerated people. e suggests that when those who are incarcerated are labeled as “criminals” and “prisoners,” the words become identities. This means “prisoner” works similarly to words like “mother,” “father,” “teacher,” or “doctor,” but in this case, the labels justify and excuse inhumane treatment. They also act to categorically divide people, allowing those who have not been personally impacted by the carceral system to distance themselves from the circumstances of those incarcerated.

In Metropolis, the labels of “criminal” and “prisoner” are called into question as incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people speak about an area of their creative expertise, from drawing comic books to writing poetry. In the sound installation, the voices of these individuals occupy space in the museum but are not seen, highlighting their unacknowledged presence and contributions in society. According to DeWeaver, these “disembodied voices, traveling across space and time and speaking,” are also a reminder that, “our bodies are not there, our bodies are not in society.” DeWeaver discusses Prison Renaissance’s unique position as an organization for and led by incarcerated people and their focus on empowering incarcerated individuals in the video below.

Reflect

Emile discusses the importance of redistributing power for the system to change. Can you think of other spaces or scenarios where you would like to see power redistributed? What kind of change might that bring about?

How Are Artists Connecting Inside and Outside?

“I believe that the prison system is like a social cancer: we should fight to eradicate it but never stop treating those affected by it..”—Angel E. Sanchez

"Carceral aesthetics offers conceptions of relationality that disavow the systems of value/worth, criminalization, and punitive governance."—Nicole Fleetwood

In her recent book, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, Nicole Fleetwood draws attention to “relational practices that connect imprisoned people to larger worlds and possibilities.” Several of the artists in Barring Freedom use different strategies to bridge the distance between the free and the unfree.

Maria Gaspar’s On the Border of What is Formless and Monstrous, 2016, uses a combination of sound and video to creatively make the walls of the prison porous, breaking down the distinctions between inside and outside. In the interview below, Gaspar discusses her experiences growing up in the neighborhood where Cook County Jail is located in Chicago. She talks about how her proximity to the jail, including a visit as part of a school trip, fueled her curiosity and desire to understand the prison system.

In an article published in Harvard Law Review, formerly incarcerated lawyer Angel E. Sanchez narrates his own experiences of incarceration and advocates for the importance of first-person storytelling by those who have experienced or been closely affected by incarceration. This is the approach embraced by filmmakers Dee Hibbert-Jones & Nomi Talisman as they draw attention to the ripple effects of the death penalty on families and communities. In their films, Hibbert-Jones and Talisman use first-person accounts to place the convicted within their network of loved ones and explore the multiple layers of injustice in capital cases. Their animated documentary Last Day of Freedom follows the personal testimony of Bill Babbitt, the brother of Vietnam veteran Manny Babbitt, who was sentenced to death for murder. In our interview below, the filmmakers discuss the importance of storytelling and of the role of animation in helping audiences connect with Bill.

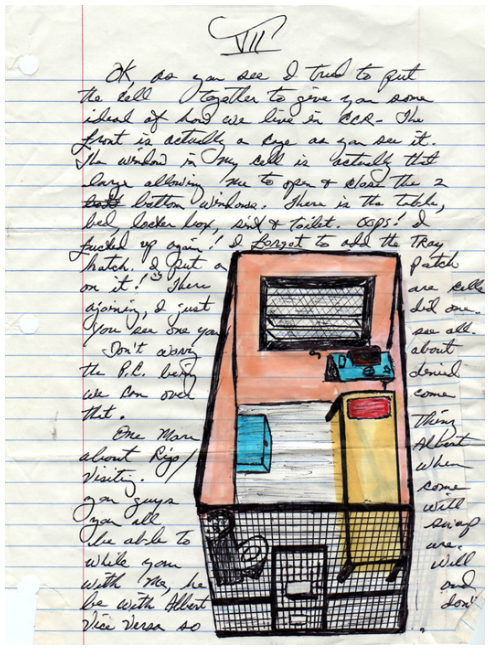

The House that Herman Built, 2008, by jackie sumell documents the 12-year friendship between the artist and Herman Wallace, who was held in solitary confinement for forty-one years. Wallace, who died in 2013 three days after he was released from prison, was one of the “Angola 3,” three men whose solitary confinement at the Louisiana State Penitentiary (also called Angola) became a rallying point for advocates fighting abusive prison conditions around the world. His friendship with sumell began when she wrote to Wallace and asked him, “What kind of house does a man who has lived in a 6’x9′ box for over thirty years dream of?” Over the course of hundreds of letters, the two designed a dream house for Herman.

In the gallery, sumell displays a wooden model of their final design built from his drawings, alongside a replica of Wallace’s cell and a selection of the letters they wrote. These letters are both the material on which the project took place and the relational heart of the project. In her recent participatory project Solitary Garden, sumell invites people outside of prison to begin collaborative relationships with individuals in solitary confinement. At UC Santa Cruz, this has led students and others to grow a garden with Tim Young, who is currently incarcerated in San Quentin. Read a selection of Tim’s letters written for Solitary Garden, including ones documenting his experiences during the Coronavirus pandemic, here.

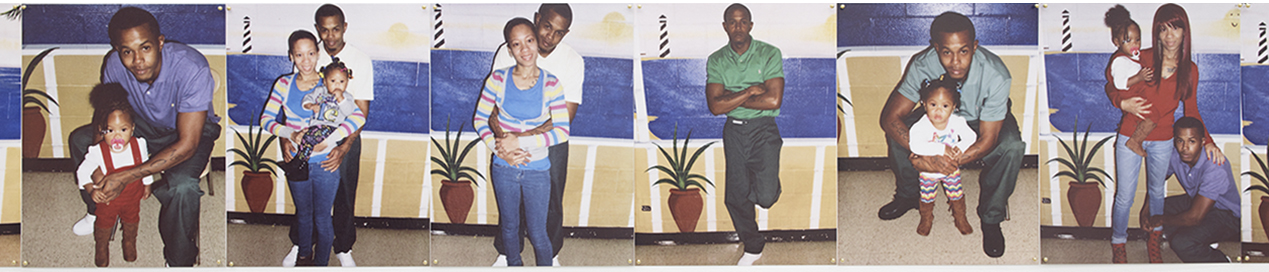

In addition to letters, prison photos also offer a connection between incarcerated individuals and their outside communities. Deana Lawson’s Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family is an appropriated series of prison portrait photographs taken over two years of the artist’s cousin, Jazmin, and Jazmin’s partner, Erik. The family poses in front of a painted mural that, according to Nicole Fleetwood, “represent[s] a sense of nonconfinement, a lack of bars, boundaries, borders.” Behind these images, is the ongoing emotional labor of those who refuse to let their loved ones be disappeared into the prison system.

Reflect

How do these artworks challenge or align with your own understanding of or experiences with the U.S. incarceration system?

What Do Materials Have to Tell Us?

Pause

This section discusses three artists who use materials from within the prison to make sculptures. Before reading about their practices and reasons, why do you think they might do that?

“If they found a calendar in one of our cells, even a homemade one, they tore it up and threw it away. I never knew why. I wondered if it was because they wanted us to lose track of time, another way to break us.” —Albert Woodfox

As Albert Woodfox, another member of the “Angola 3” who spent 43 years in solitary confinement, documents in his memoir, Solitary, prison life is marked by extreme deprivation. Individuals are denied access to even seemingly benign items like calendars, making the rules often feel arbitrary and only in place to make those incarcerated feel powerless. To communicate the embodied experiences and deprivations of incarceration, Sherrill Roland restricts his artistic practices to using only materials that were available to him while incarcerated. For The Jumpsuit Project, Roland performs while wearing an orange jumpsuit similar to that which he wore during his time inside and restricts his movements to a 7' x 9' rectangle that mirrors the dimensions of his cell. In the series Contraband, he draws attention to common materials that were not allowed but that he managed to obtain and hide. These include such basic necessities as a ballpoint pen or dental floss. In the video below, Roland elaborates on these material choices and constraints.

In Tar Ball, Levester Williams uses unclean bedsheets from a Virginia correctional facility coated in tar to create his visceral four-foot sculpture. By keeping the sheets unclean he conserves traces of those who slept on them. “I wanted to, in essence, preserve the humanity of, the individuals who last used those bed sheets.” In the clip below he discusses how this gesture of care and respect for incarcerated men is related to his personal experiences and articulates his demand to be treated with dignity and respect.

Lastly, in the interview excerpt below, Hank Willis Thomas reflects on his use of decommissioned prison uniforms in a series of quilts. In Bars, Thomas has sewn the uniforms together so that the bars of the uniform become the bars of a cell. The work invites reflection on the visual power of the striped prison uniform to separate and mark those who are incarcerated as criminals; though the stripes are no longer used in U.S. prisons, their image haunts our imaginaries. Thomas remarks upon the past life of his materials and speaks candidly about his discomfort with using them, “I don't know if anyone should have the right to be making art literally with someone else's sweat.”

Reflect

Hank Willis Thomas raises an important question about the ethics of making art about the suffering of others. He ends “Am I worthy? And do I have a choice?” What do you think are the responsibilities of artists (visual artists, writers, musicians, filmmakers, etc.) in regard to stories of oppression and injustice?

Cited Readings

- Davis, Angela Y. Are Prisons Obsolete? New York: Seven Stories, 2003.

- Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2020.

- Sanchez, Angel E. “In Spite of Prison.” Harvard Law Review 132, no. 6 (April 2019): 1650–83.

- Woodfox, Albert. Solitary. New York: Grove Press, 2019.

Other Resources

- Bhalla, Angad Singh. Herman’s House. First Run Features, 2013.

- The Angola 3

Other Study Guides